“If you love me, you will keep my commandments.”

“If you love me, you will keep my commandments.”

John 14:15

+ + +

Gracious God,

you have given us your Spirit as our advocate and guide

that we might abide in you and you in us.

Grant us courage and faith to follow where you lead,

to obey your commands,

to love as you love.

+ + +

A message from Sunday morning

The Sixth Sunday of Easter, year A

May 17, 2020

John 14:15-21: “If you love me, you will keep my commandments. And I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate, to be with you forever. This is the Spirit of truth, whom the world cannot receive, because it neither sees him nor knows him. You know him, because he abides with you, and he will be in you.

“I will not leave you orphaned; I am coming to you. In a little while the world will no longer see me, but you will see me; because I live, you also will live. On that day you will know that I am in my Father, and you in me, and I in you. They who have my commandments and keep them are those who love me; and those who love me will be loved by my Father, and I will love them and reveal myself to them.” (NRSV)

+ + +

Grace to you and Peace, from God our Father and our Lord and savior, Jesus the Christ.

At first this was an emergency. As the threat of this novel corona virus grew, we had to think through what we would do in worship to limit our risk. Then, as the shut-down came, we had to quickly figure out a way to continue to worship online with the few resources we had. It was a challenge, a puzzle to be solved. And I was entirely focused on figuring out a way for us to worship – and then to do Holy Week and Easter online. I didn’t have much time to do anything else.

But now, as the days drag on, I find myself grieving the loss of something that has been so important to me for the last 42 years. I’ve been a pastor of the church. And it’s been a great privilege. I’ve been able to embrace those who grieve. I’ve been able to hold hands and pray for those in need. I’ve been able to lay my hands upon those in the hospital and say the blessing. I’ve been able to lay hands upon the newly baptized, and upon confirmands at their confirmation, and upon the dying with the last rites. I’ve been able to hold a child in my arms and walk her through the sanctuary following her baptism, introducing her to all those who now share in her spiritual life and growth. Now all I have is this moment when I can see a few of you on the screen and talk to you about a text that seems far away from the realities of our daily life

I’m not able to invite you to be involved in care for others. I’m not able to celebrate silly occasions like talent shows or youth dinners. There are no confirmation retreats. We can’t share a moment over a cup of coffee. There are no delightful surprises that Tom has brought donut holes or that Elaine has made Kringle, or that Yolanda and Bill have made those amazing little sandwiches. And I don’t see an end.

At some point it might happen that a few would begin to gather in the building and I could at least see faces – but those faces are likely to be covered by masks. And we are going to have to sneak in and out without getting closer than six feet to each other.

We are reduced to waving at each other rather than shaking hands.

Jesus touched the man with leprosy. He made mud and put it on the eyes of the man born blind. He took the synagogue ruler’s daughter by the hand and raised her up. He touched the bier upon which lay the body of the widow’s son.

Jesus broke bread. He washed feet. And shall I risk any of that? I will not be able to sit with children for a children’s sermon. I cannot take a child’s hand as we go outside to look at the tiny seeds of the Redwood trees and think about how they grow into giants.

I stand here on Sunday mornings and look out into an empty sanctuary. I know you are there. I know we are still connected in spirit. I know we are still gathered around this wondrous book and a table set with bread and wine. And I know we are keeping our physical distance because we care for one another. But I would like to be in your living room or at your dining table or watching a football game together. There are other words to be spoken, stories to be heard, lives to be shared.

I am struggling. So many simple and ordinary joys are gone. And I don’t want any more losses.

I want to sing the liturgy. I want to feel the energy of an Easter crowd. I want to see familiar smiles. I want to share coffee and talk about the Sunday crossword puzzle. I want to hear Natalie’s voice and see her face in the office. I want to feel like this place is a sanctuary in all the best sense of that word.

I want to listen to the Swedish children’s choir singing in the next room when I’m here on a Saturday working on the sermon. I want to hear the laughter of children on the playground during the week. I want to chat with parents from the neighborhood who bring their children to play. I want to pet the occasional dog being walked. And, yes, there were times I needed to hide away in my basement office for some quiet uninterrupted time to study or write, but the music school was banging their drums in the next room, and there were children walking back and forth before my window with whom I could smile and wave. I wasn’t just alone in my office.

I am frustrated, frustrated that all this social distancing was supposed to buy time for our leaders to put a plan in place – to get the equipment we needed, to get the testing we needed, to establish a process and hire the people that were necessary to trace and contain this virus. But we have fumbled that effort. We have wasted that time. And it is the weak and the vulnerable and the poor who have born the worst of it. Some are being forced to go back to work no matter how risky it is for them – or how fearful they might be – or how many children or seniors depend on their care – they are forced to go back or lose their unemployment coverage (if they’ve been able to get it).

On Saturday evening last week, the death toll from COVID-19 stood at 79,696. Last night it was 89,420 – almost 10,000 more. 10,000 more families have lost loved ones in this last week despite the heroic work of doctors and health workers. 10,000 more have had to die alone, without a parent or a child or a partner to sit at their side and hold their hand. And the best we can say is that maybe it will hold steady – not because we are helpless before this virus, but because we fumbled the ball and turned it over on the ten yard line. We have more deaths than any country in the world.

10,000 more this week. 80,000 thousand people so far. Each with family and friends and neighbors. Each with lives they have touched. Each with contributions they have made. Each with stories to tell. Each with sadness and loss left behind.

And for each of those 10,000, there are doctors and nurses whose hopes and spirits have been worn down because they couldn’t save them.

We raised an army and built ships and airplanes to fight fascism in Europe and imperialism in Japan. We created a Marshall plan to rebuild Europe. We kept Berlin alive with an airlift – planes taking off and landing every 90 seconds, night and day, when the Russians closed the rail lines. We went to the moon. We ended polio. We ended smallpox. We should have been able to fight this, not throw up our hands and say tests aren’t important and masks are a socialist plot.

I appreciate the fact that on Friday mornings the CBS morning news is beginning to show some of the people who are perishing. We talk too often about numbers and not often enough about the people whose lives are being stolen away. Five names, one day a week, however, is not enough when 10,000 are dying.

Paul and Iris shared with the council this week that their nanny’s sister has died from this Corona virus. These are not numbers; these are real people. We should not have to fight to have them recognized as such.

The children of Syrian refugee camps are also real people. As are the children of the border detention centers. As are the children of Flint, Michigan, and every other place where people are not only absent from our minds, but absent from our hearts.

When Jesus says to us this morning: “If you love me, you will keep my commandments,” he is asking an important question.

The way you express a conditional statement in Greek – an “if/then” statement – can tell you what you expect. The grammar reveals whether the “if” part of the statement is true or not. So, one way to express this in Greek says: “If you love me (and we know that you do), you will keep my commandments.” Another way says: “If you love me (and we know that you don’t), you would keep my commandments.” And the third possibility says: “If you love me (and we don’t know whether you do), you will keep my commandments.”

When Jesus says this to his followers, he uses this third way. The statement doesn’t assume that we love Jesus. Whether we do or not will be revealed by whether we keep his commandments.

The word ‘commandments’ is in the plural. It refers to all that Jesus has taught. But there is really only one commandment. That is the commandment Jesus has just given moments before when he washed the disciples’ feet and said: “A new commandment I give you, that you love one another.”

And let’s not be mistaken. When Jesus talks about loving one another, he isn’t drawing that circle around a few close friends. He is drawing that circle around the whole human community.

If you love me, you will show faithfulness to all I have taught. If you love me, you will treasure and observe my teaching. If you love me – if you feel an obligation and allegiance to me as if to a member of your own family – you will keep my commands, you will show faithfulness to all, you will treat every person as if they were family.

Jesus ends this passage with the same point he made at the beginning: “They who have my commandments and keep them are those who love me.” Fidelity to Jesus means fidelity to all.

Jesus will not leave us orphaned. (I rather liked the old translation: “I will not leave you desolate,” but the word does mean ‘orphaned’.) We are not abandoned. We are not alone. Jesus is speaking to his disciples on the night he will be taken by the mob and thrust before Pilate and impaled upon the cross. Jesus knows what is coming, but he will not leave his disciples abandoned and alone. He will come to them. It is a reference to that Sunday evening when Jesus revealed himself in their midst. And Jesus will also come to them – come to us – in the Spirit that he breathed out upon his followers.

The Spirit is the living presence of Jesus in the community. It is our ongoing teacher and guide. It is the breath of life and font of grace. It is the wonder of inspiration and the courage of love. It is the comfort that comes to the downtrodden through simple acts of kindness and bold words of forgiveness – or simple words of forgiveness and bold acts of kindness.

The Spirit is the ongoing presence of Christ in our midst, the ongoing presence of Christ in the world.

It is a truthful Spirit. It inspires no deceit, tells no lies, creates no illusions. It doesn’t deceive or manipulate or confuse. It does not lead to doubt or despair. It inspires mercy and forgiveness and courage and truth. It inspires love and patience and kindness. It inspires hope and joy. It carries us from the sorrows of the world to the joy of God’s table. It carries us from the brokenness of the world to a new birth from above. It carries us from a wedding that has run out of wine to the eternal wedding feast. It carries us from our isolation into community. It carries us from death into life.

Amen

+ + +

© David K Bonde, 2020. All rights reserved

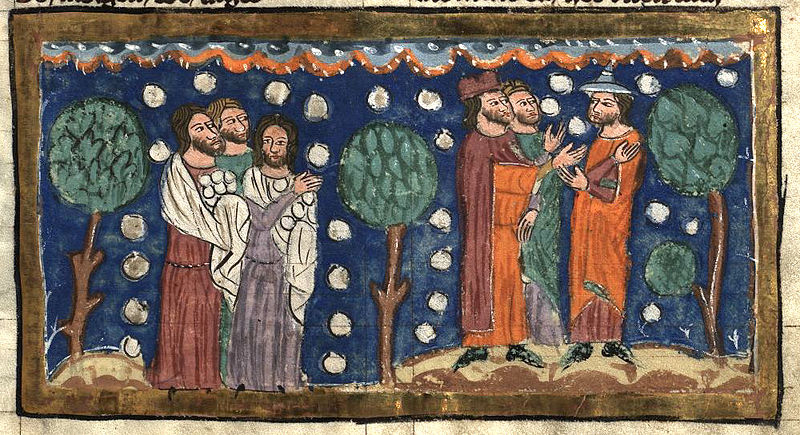

Image: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Christ_Taking_Leave_of_the_Apostles.jpg Duccio di Buoninsegna / Public domain.

Scripture quotations are from New Revised Standard Version Bible, copyright © 1989 National Council of the Churches of Christ in the United States of America. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

It would be nice if we could just say the ancient words and all be carried along by their familiar comfort. But they aren’t familiar to us anymore. And they are tainted by the negative perceptions of all religion as partisan and judgmental and even hateful and violent, despite the fact that Jesus was not the founder or reformer of religion but its victim.

It would be nice if we could just say the ancient words and all be carried along by their familiar comfort. But they aren’t familiar to us anymore. And they are tainted by the negative perceptions of all religion as partisan and judgmental and even hateful and violent, despite the fact that Jesus was not the founder or reformer of religion but its victim.